It's hard for me to name a favorite London museum. Let's just say that the Tate Britain is one of them. For me, a visit to the Tate is a walk down Memory Lane, enjoying my favorite, painted hits. So, for my last full day in London, I went to visit the Tate.

The museum claims to present "500 years of British Art"—and its collection is, indeed, vast and wonderful. But how "British Art" is defined seems rather elastic to me; many of the museum's works have been sculpted or painted by non-Brits. Perhaps a work of art (even one by a foreign artist) qualifies as "British" if it was conceived on British (or United Kingdom) soil? Or perhaps it's considered "British" if the artist lived in the UK for a period of time? As for me, the end of the day, I just want to see beautiful art—and the Tate Britain really scratches that itch.

Shown above, the grand "central hallway" which divides the galleries on either side of the building. In truth, my initial thought was, "What a waste of precious space! Fill it with art!" But, as I walked along the barren hallway, I began to appreciate the "palette cleansing" effect of the space. It helped clear my mind before I popped into the next gallery.

Amongst my (many) favorites at the Tate is a nice collection of pictures by the (American) artist, James Abbott McNeill Whistler (1834-1903). Shown above, a stunning Impressionist riverscape titled Nocturne: Blue and Gold—Old Battersea Bridge. It was painted between 1872 and 1875. Its simple composition and tight color palette is, nevertheless, bold and confident. Also note that Whistler applied his unique "butterfly monogram" (which often appears on his paintings or prints) upon the right, vertical side of the gilded frame. This suggests that the artist was involved in selecting or designing the framing for this picture.

Whistler was also a wonderful portraitist. Shown above, a portrait of an eight year old girl entitled Harmony in Grey and Green: Miss Cicely Alexander. It was painted in 1872-1874, commissioned by the girl's father, a banker. He had an interest in Japanese decorative arts—as did Whistler, who accommodated by placing daisies and butterflies into the picture. Whistler himself designed the girl's dress and had the rug specially-ordered for the painting. The patient young girl sat through more than 70 sittings while the painting was created.

This sensational picture, The Lament for Icarus by Herbert Draper (1863-1920), captures the mourning of water nymphs after the young man had crashed, having dared to fly too close to the sun. Actually, before I had ever seen this actual painting, I had seen the preparatory sketch—owned by a late friend who had it mounted in his guest room. The picture was first exhibited in 1898. Mythological themes (and the lessons they taught) were important in Victorian society and its artworks. Aside from the lesson, this picture is wonderfully dark and sexy.

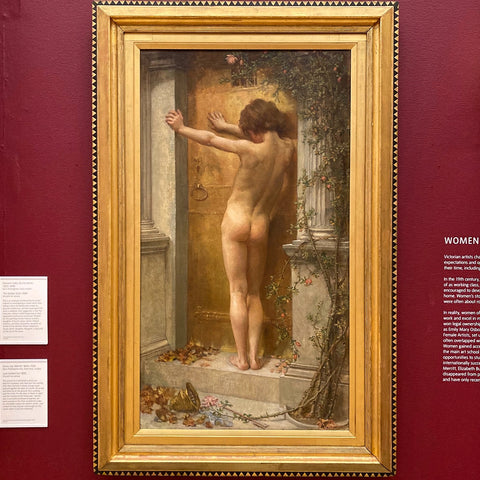

Another Victorian "message" picture is the one above, titled Love Locked Out, painted by Anna Lea Merritt (1844-1930). Merritt was born in Philadelphia. Her Quaker family moved to Europe in 1865, where Merritt studied art. In 1870, her family moved to England where she met Henry Merritt. They married six years later—though, alas, he died three months after their wedding.

Merritt painted Love Locked Out in 1890 as a tribute to her deceased husband: Cupid, who has dropped his bow and arrows, struggles to open the Door of Death—attempting valiantly to reunite the two lovers.

Merritt planned to cast the image in large-scale bronze, as a funerary monument, however, it proved too expensive for her to fabricate. She refused to allow Love Locked Out to be reproduced for she feared people may misinterpret the picture's meaning. In time, however, she must have relented, for I have collected and sold several framed sepia prints of the image (probably purchased at the Tate in the Teens or Twenties).

Frederic Lord Leighton (1830-1896) revolutionized British sculpting with this work, An Athlete Wrestling with a Python (1877). The classical theme, enhanced with naturalistic realism (muscles, tension, texture) birthed the movement called New Sculpture. Leighton helped invigorate this renaissance of British metal sculpting which employed a modern, energetic style (yet still relied on classical, mythological or poetic themes). In addition to sculpture, Leighton was an excellent draughtsman and painter.

Leighton came from a wealthy family. His grandfather had been physician to two Tsars. He was able to have this plaster sculpture cast in bronze without requiring a wealthy patron to commission it. Leighton simply paid for the casting himself.

Leighton never married. His home—now the sublime Leighton House Museum in London—was also his studio where he entertained a coterie of young, handsome men.

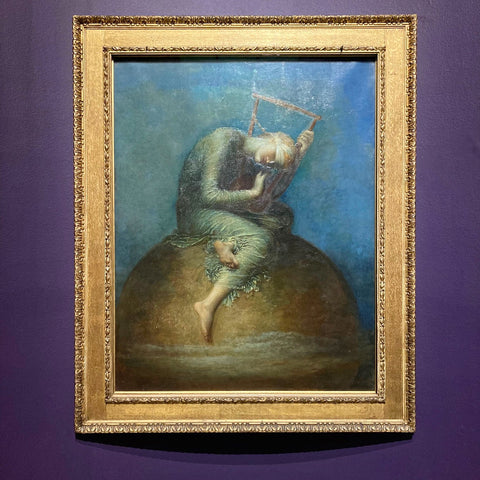

George Frederic Watts painted Hope, a Symbolist picture, in 1886. He painted (at least) four versions of the work, donating this one (the second version) to the Nation in 1897. In this image, the personification of Hope is depicted as a blindfolded woman, clutching her lyre on which only one string remains. She holds her ear close to the instrument, struggling to hear the sound.

This image was very popular with the public. Printed reproductions of the painting were sold in museum gift shops and could be found all over the world. Over the years, I have sold several such framed prints—which likely were museum shop souvenirs from the first quarter of the Twentieth Century.

Henry Scott Tuke (1858-1929) was born in York, though his family moved to Cornwall when he was a year old. He worked closely with the Newlyn School, in Penzance, Cornwall. Tuke painted in two distinct styles: polished maritime paintings (often commissioned portraits of sailing ships) and impressionist images (with spontaneous and exuberant brushwork) of nude youths swimming, fishing or sunbathing on boats or upon the seashore. A number of local Cornish boys modeled for him, providing a chance for these working lads to make a little extra money. Most of these models were called-up for service during World War One—and several of them did not return.

The picture above, called August Blue, was painted in 1893-94. Four boys swim, fish and relax on the row boat in Falmouth Harbor, Cornwall. In this painting, Tuke exhibits his mastery of capturing light as it glances off water and skin. August Blue was exhibited at the Royal Academy in the Summer of 1894 and was immediately purchased by the Tate (where it is still exhibited).

Today's viewers are more likely (than viewers in Victorian England) to assign a homoerotic vibe to the painting. And Tuke, who was gay, was indeed drawn to male beauty. But to call the paintings prurient (or worse, obscene) is unfair. The boy's privates are almost never visible and the boys are never engaged in any activity which is remotely sexual. Many of the figures show their backs (sometimes buttocks) to the viewer. Tuke's pictures convey an athletic masculinity, healthy and vigorous. To the Victorian mind, nude youth (provided it was tastefully modest) captured the purity of youthfulness—an unselfconscious embrace of nature and beauty in the healthful outdoors.

Tuke was a prolific painter. His "mainstream" maritime images provided a good income—allowing him to travel abroad and to support his more private endeavors (the nudes). In the Thirties, Tuke's works fell out of fashion. He was rediscovered in the Seventies, due in part to the emergence of openly gay collectors. Elton John has a substantial collection of Tukes and the artist has developed a cult following amongst the gay cognoscenti.

Though our Greenwich Village store is now permanently closed, LEO Design is still alive and well! Please visit our on-line store where we continue to sell Handsome Gifts (www.LEOdesignNYC.com).

We also can be found in Canonsburg, Pennsylvania, at The Antique Center of Strabane (www.antiquecenterofstrabane.com).

Or call to arrange to visit our Pittsburgh showroom (by private appointment only). 917-446-4248